Most countries, at all levels of development and in all regions of the world, today face a double burden of malnutrition: The coexistence of nutritional deficiencies such as stunting and micronutrient deficits on the one hand, and overweight, obesity, and noncommunicable diet-related diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes and hypertension on the other. Not only is this double burden widespread, it exists at the individual, household, and population levels.

The consequences of malnutrition are long-lasting and costly. Undernutrition can set in motion a lifetime of adversity, including delayed child development, poor school performance, and lower earnings. Adults who have suffered from undernutrition early in life are at greater risk of overweight, obesity, and diet-related NCDs, especially if they live in countries undergoing the nutrition transition and related spread in obesogenic environments. Overweight and obese adults are more likely to suffer from NCDs, causing a host of problems for affected individuals, families, and communities, including increased mortality and rising healthcare costs.

Traditionally, the development community has treated these problems of undernutrition and overweight/obesity separately. Given the new nutrition reality, however, we must begin to shift toward a more integrated strategy—especially as evidence mounts that without such a shift, we risk creating a new problem (overweight/obesity and NCDs) in the process of trying to solve an old one (food insecurity and undernutrition).

Food-assisted maternal and child health and nutrition programs

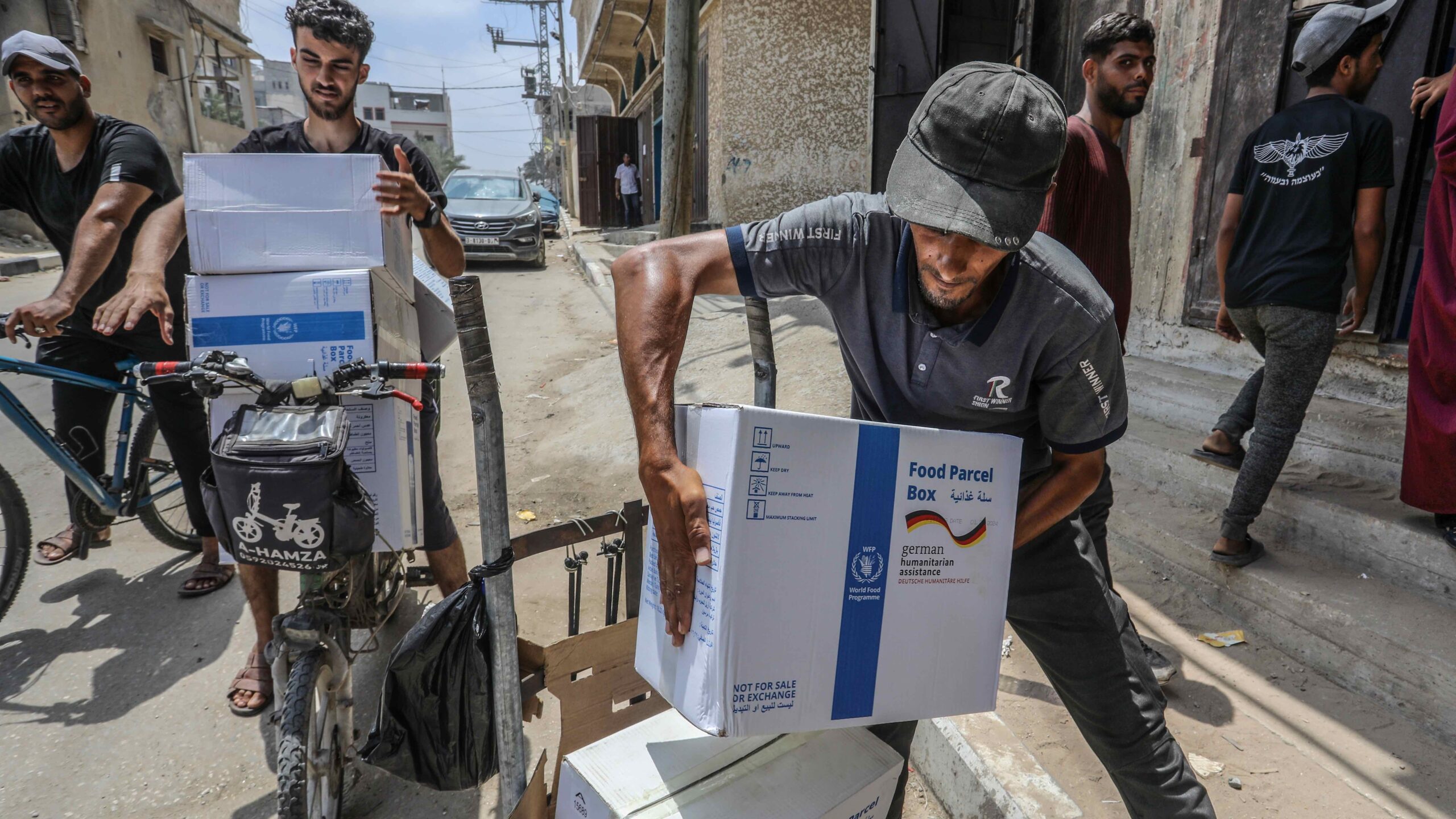

Food-assisted maternal and child health and nutrition (FA-MCHN) programs provide a good example of interventions that are effective, but under certain conditions may have unintended consequences. FA-MCHN programs have been widely used to reduce household food insecurity and maternal and child undernutrition. These programs typically include food transfers and a package of health and nutrition interventions. Recent evidence shows that these programs can effectively improve nutrition among mothers and their children.

Yet food and cash transfer programs that increase household income and access to food have also been shown to increase the risk of excessive energy intake and unhealthy weight gain, especially in populations that are undergoing a rapid nutrition transition and are not suffering from food insecurity (defined here as not having access to sufficient calories). Underscoring this point are findings from our recent evaluation, published in the Journal of Nutrition. The FA-MCHN intervention we evaluated in Guatemala achieved its goal of reducing stunting but also contributed to maternal postpartum weight retention.

PROCOMIDA: A qualified success

Guatemala has one of the highest stunting rates in the world. Alta Verapaz is among the poorest departments in the country, with low literacy rates, poor housing conditions, and limited access to electricity and other services. Half of all children under 5 there suffer from stunting, while 47% of women between the ages of 15 and 49 are overweight or obese.

In 2009, USAID and Mercy Corps launched the five-year Maternal-Child Diet Diversification Program (PROCOMIDA), which aimed to reduce stunting in Alta Verapaz. The PROCOMIDA intervention included food rations, behavior change communication (BCC), and activities to improve the implementation and use of government-funded health services. Our evaluation of PROCOMIDA found that it succeeded in reducing stunting. Notably, providing a large family ration increased program participation and contributed to greater program impacts. But given that PROCOMIDA was designed to address childhood undernutrition in an area also grappling with a high prevalence of overweight and obesity, how (if at all) did it affect participating mothers’ weights?

To find out, we used the same cluster-randomized controlled longitudinal study design used to assess the impact on stunting.

We discovered that the program increased mothers’ weight retention in the 24 months after childbirth. The largest impact was found among those receiving the full family ration: The program resulted in an average weight gain of nearly 600 grams (1.3 pounds) at 24 months postpartum among women in this group. Since unhealthy weight is associated with higher mortality and other health issues, the higher average weight found in the intervention group compared with the control suggests that the program unintentionally caused harm to beneficiary women.

What explains this impact on women’s weight? The association between the size of the family ration and the size of the impact on weight suggests that the gain resulted from an increase in women’s dietary energy intake. A qualitative substudy found that, compared with the control group, program beneficiary families consumed program ration foods more frequently, defying our expectations; they reported eating more eggs, local plants, and some vegetables, but also more energy-dense foods such as pasta and sugar.

Implications for program design

Our findings demonstrate that in contexts like rural Guatemala, where the nutrition transition is accelerating and overweight and obesity are endemic, program planners must consider the possibility that the types and quantities of food that will maximize program participation and impacts on child stunting may worsen the problem of maternal overweight and obesity. They should widen the scope of FA-MCHN programs beyond a single aim and explore whether other transfer modalities (such as cash or vouchers that can be used for fresh food purchases) combined with strong BCC would produce more desirable outcomes.

Double-duty actions—programs and policies that aim to simultaneously address problems of undernutrition and overweight/obesity and diet-related NCDs—have been proposed as a holistic way to tackle malnutrition in all its forms. At a minimum, these double-duty actions require that current nutrition programs and policies designed to address poverty, food insecurity, and undernutrition do not inadvertently exacerbate problems of overweight and obesity and NCDs.

Jef Leroy and Deanna Olney are Senior Research Fellows with IFPRI’s Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division (PHND) and Marie Ruel is Director of PHND; they were the principal investigators in the study. Tracy Brown, IFPRI Senior Editor, prepared the text of this post.

This post reviews results from “Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of the Preventing Malnutrition in Children under 2 Approach,” a USAID-funded research project in Guatemala and Burundi. The CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH), led by IFPRI, also provided support. Opinions expressed are the authors’.

Read our related three-part blog series on results from this project in Guatemala and Burundi here, here, and here.

Read the open-access article “PROCOMIDA, a Food-Assisted Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition Program, Contributes to Postpartum Weight Retention in Guatemala: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Intervention Trial” in the Journal of Nutrition.