Three months after the outbreak began, it is easy to see the COVID-19 pandemic for what it is: A human tragedy that constitutes the most severe blow to the global economy since the Second World War. It has swiftly overwhelmed the health systems of all nations—developed and developing—producing social and economic impacts that will be unprecedented in scale.

For the poorest countries, however, the full danger is only just coming into view. They will face the crisis from a position of profound disadvantage: Their health systems are fragile, their access to critical medical supplies is tenuous, their economies are less resilient and heavily dependent on trade.

They could soon come under siege on all fronts—and a health, economic, and social catastrophe here would be felt across the world. It would fan the spread of the virus and imperil prospects for a global economic recovery.

Cooperation to help these countries limit the harm is not just a moral imperative—it is in the world’s interest. The policy choices we make today will have enduring effects on the ability of developing countries to respond to the health and economic crisis.

Too many countries are adopting policies that risk disrupting access to medical supplies and destabilising food markets. We know from history that such policies aren’t just ineffective—they actually aggravate the harm they’re intended to ease. It’s smarter to take a coordinated approach to boosting production and meeting the needs of the most vulnerable.

So far, the vast majority of reported COVID-19 infections has been in developed countries—although the numbers in developing countries could rise considerably in the coming months.

The economic harm, however, is spreading: Simultaneous demand and supply shocks are rippling across borders through their effects on travel, trade, finance, commodity markets, and investor confidence. Seventeen countries with the highest number of COVID-19 cases are vital nodes in global trade networks, magnifying the economic fallout for developing countries.

The pandemic has already created a global shortage of medical supplies. Increasing restrictions to exports exacerbate the shortages and drive prices up. At the World Bank Group, we recently created a new database to track the effects of such policies.

It highlights the vulnerability that developing countries face regarding medical supplies: the 20 developing countries with the highest number of COVID-19 cases derive 80% of critical COVID-19 products from just five economies.

Our analysis shows, moreover, that current export restrictions are likely to increase prices of medical masks by more than 20%. If restrictions escalate, prices would shoot up by over 40%.

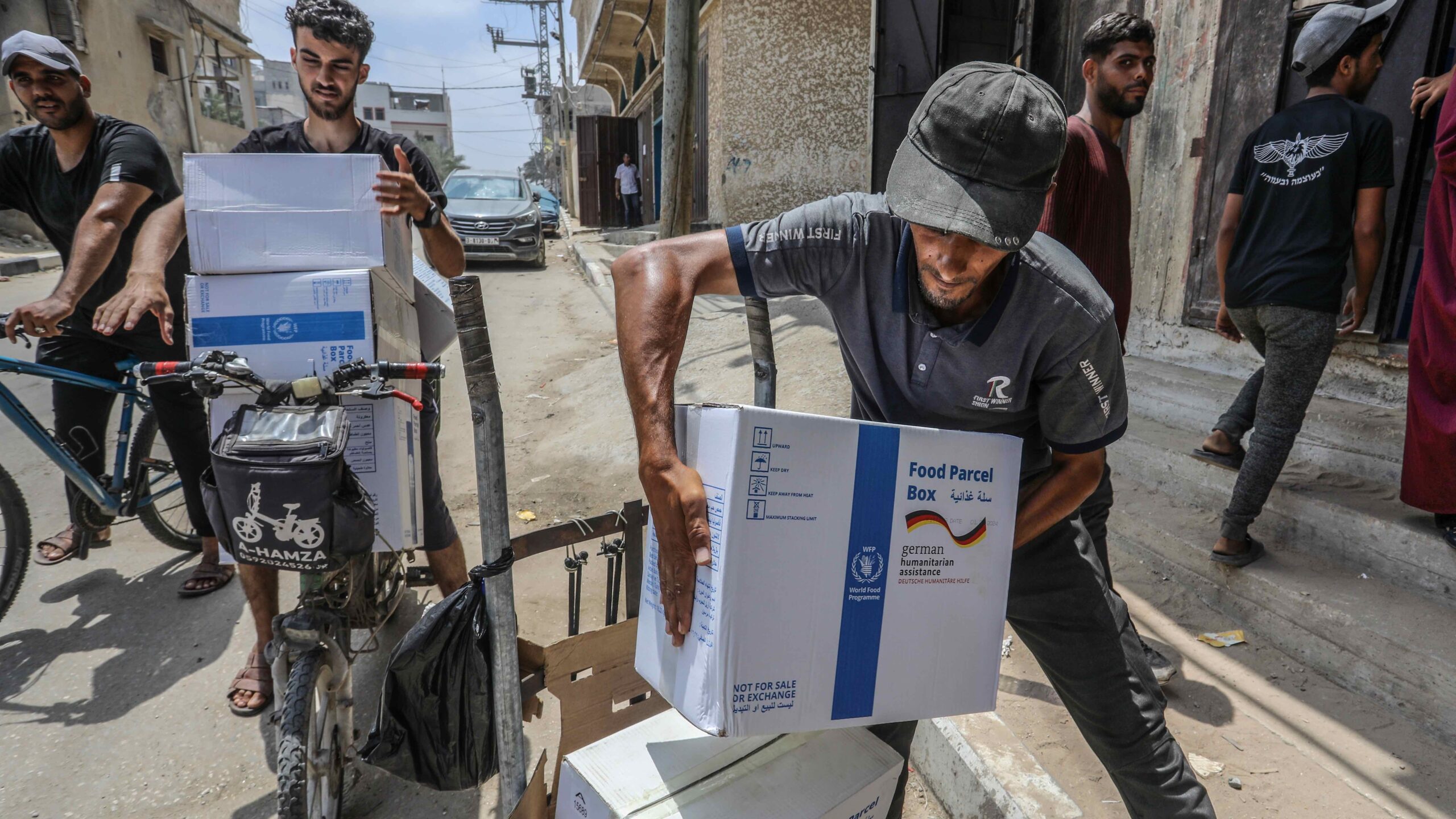

Food shortages could be next. That alone should give us pause—because production levels of food staples in 2020 are expected to be near all-time highs. Supply is thus not a problem at this time.

But shortages could result from disruptions in supply chains, labor shortages as people become sick, and reduced activity by small and medium enterprises (SMEs) – many of which could go out of business. For example, China’s exports of agricultural goods in the first two months of the year declined 12% year-on-year.

Here again a handful of countries are going it alone. Restricting food exports to boost domestic availability is exactly the wrong response under the circumstances. As we learned from the 2008-2011 food crisis, such measures increased global prices by 13% on average—and by 45% for rice.

The poorest countries, which rely heavily on food imports, would be hurt the most. Developing countries on average derive 80% of their food imports from just three exporting countries. For fragile and conflict countries the proportion is more than 90%, making them even more vulnerable to policy changes by exporting nations.

A consistent global approach—one that emphasises international cooperation and an open and rules-based trading system—will be essential to ensure a quick response as rising infection rates and economic pain spreads to the developing world from advanced economies.

That is why I recently urged trade ministers from the Group of 20 nations to immediately undertake concrete actions while pushing for parallel actions by all members of the World Trade Organization:

- Refrain and discipline new export restrictions on critical medical supplies, food or other key products.

- Eliminate or reduce tariffs and unnecessary barriers on imports of COVID-19 products, food, and other basic goods.

- Ensure that vital products can cross borders safely. Secure continued access to capital and trade financing to SMEs.

All governments should act promptly to defuse the danger of shortages of critical products. Coordination on procurement of such supplies will be essential to boost production in ways that are cost-effective and ensure that supplies flow quickly—from areas of surplus to areas of shortage.

In this area, the World Bank is taking on a particularly proactive role: we are offering Bank-Facilitated Procurement (BFP) to help our client countries access critically needed medical supplies and equipment, for no fee.

We will assist in identifying existing suppliers with available stock and negotiating prices and conditions. Borrowers will then sign and enter into contracts themselves, including assuring relevant logistics with suppliers.

In addition, through our SME lending programs we are supporting the retooling of production capabilities towards medical goods, where feasible.

In all our work, our priority is to provide fast and flexible responses to limit the impact of COVID-19 while strengthening international cooperation. Last month, we approved a $14 billion Fast Track Facility to assist countries and companies in their efforts to prevent, detect, and respond to the pandemic, and includes the trade financing and credit facilities from IFC.

As we enter the next phase of response on recovery and coming out stronger from the crisis, the right policy actions and international cooperation is even more important.

The WBG and the IMF have called for suspension of debt payments from IDA countries that request forbearance, so as to provide them fiscal space.

Furthermore, over the next 15 months, we stand ready to provide up to $160 billion in long-term financial support to developing countries to continue supporting countries respond to the crisis and enhance resilience for recovery.

Over the past three months, the swift and indiscriminate spread of a deadly virus has banished any doubt about the magnitude of the danger it poses. Going it alone is no longer an option.

Countries that remain globally integrated will be best placed to respond effectively in the short term—and to recover more quickly in medium term. We will come out much stronger if we all work together with a clear focus on the future.

Mari Pangestu is the World Bank Managing Director for Development Policies and Partnerships and Chair of the IFPRI Board. This piece was originally published in The Telegraph.