One of IFPRI’s most important pillars is capacity building, which includes training students and government analysts alike around the world in data collection and analysis, and related research techniques.

In June, the two of us, along with IFPRI Research Analyst Rachel Gilbert, partnered with the Australian National University and the University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG) to teach a 3-day evening seminar for the Master of Economics and Public Policy program in the UPNG School of Business and Public Policy—the 40 students included many analysts from various government departments.

The course, “Describing, Transforming, and Analyzing Data Using Stata,” aimed to give participants an overview of Stata—one of the most commonly used statistical software programs for data science—so that they could use it to prepare their masters’ theses and beyond. We covered how to develop a research question, query the data, and use Stata to analyze and present results related to key policy research questions.

We also wanted to disseminate and encourage the use of data from the IFPRI Papua New Guinea (PNG) Household Survey on Food Systems (collected in May-July 2018). These students were among the first to comb through the recently collected household survey data, now publicly available.

The key findings from the survey sparked interesting discussions. The survey collected detailed data on consumption and expenditures, and the class talked about the differences in food baskets between different regions. In Madang (along the Ramu River in the northern area of mainland PNG), the sample’s food basket comprised few goods and relied heavily on starchy subsistence foods; while in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville (AroB)—an island east of the mainland of PNG—the food basket was more diverse given the area’s greater trade in exports such as cacao in exchange for marketed foods, but still relied heavily on simple starchy food groups (Figure 1).

This finding led to a discussion about poverty, and ways to understand how and why income and expenditure structures and livelihood strategies vary by survey area. Students brainstormed on how the food basket data could be paired with a variety of other survey data—including information on agricultural production, labor profiles, migration activity, and anthropometry measurements—to further understand what is driving these differences.

IFPRI

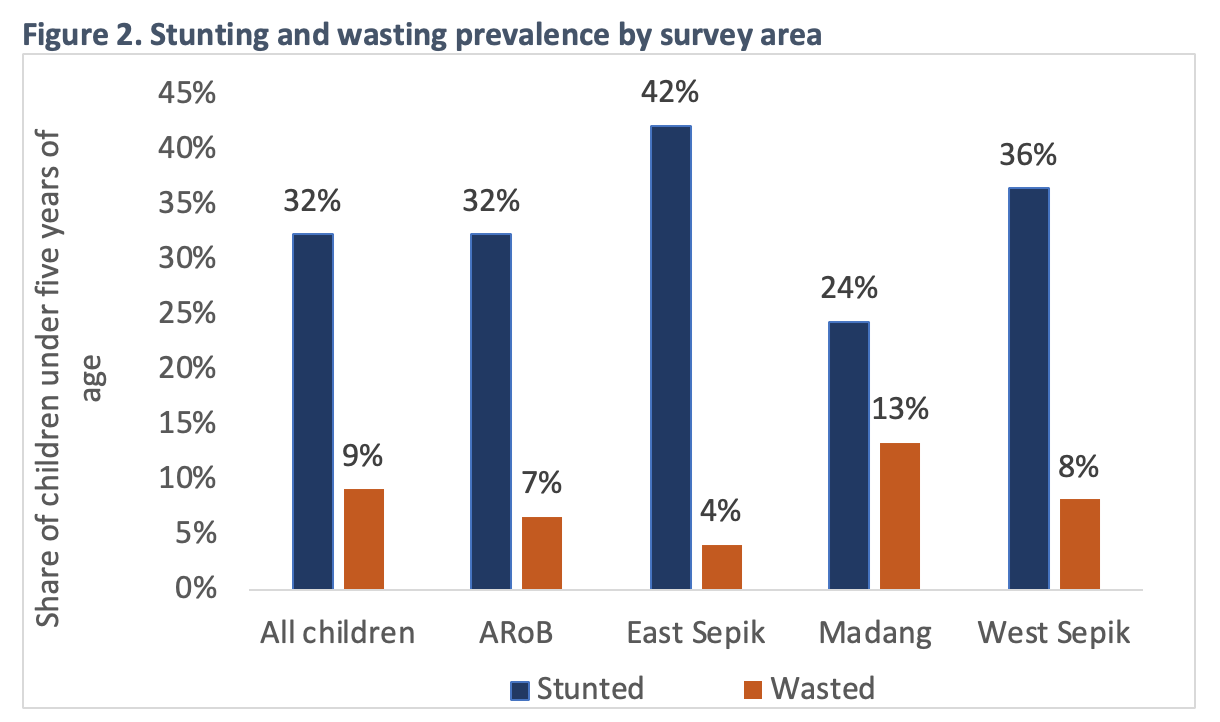

Almost all of the course participants were government analysts interested in understanding agricultural ties to overall nutrition, so we devoted a section of course material to health and nutrition indicators among children and mothers. On the second day, participants used the survey data to evaluate child growth and development outcomes.

A recent IFPRI analysis found that 32% of children under 5 years of age in the survey households are stunted and 9% are wasted. We walked course participants through the analysis that suggested that child growth is associated with the mother’s height and body mass index (BMI) in the survey sample.

This finding raises important questions for policy and program design, and we discussed potential investments and approaches to improve overall health outcomes for women and children in rural PNG. This session led to a lively debate on the best health investments, with some students advocating for better water and sanitation infrastructure, and others preferring access to better income-generating activities for households to be able to afford more nutritious diets.

IFPRI. Source: Authors’ calculations from the IFPRI Papua New Guinea Household Survey on Food Systems,

2018. ARoB is the Autonomous Region of Bougainville.

The final day of the course focused on agricultural and rural livelihood systems. Many analysts from the Department of National Planning and Monitoring and the Department of Agriculture participated in the training, and we presented recent findings from the survey on the importance of non-farm enterprises (NFE) in rural PNG.

The class discussed an IFPRI regression analysis showing that female NFE ownership is significantly associated with having experienced a drought. This finding suggests that women-owned businesses may be an important risk diversification strategy in times of climate shocks, providing an additional source of income in case of a poor harvest.

Participants actively challenged research hypotheses and analysis decisions throughout the course, and were enthusiastic about using the IFPRI survey data in their own work. We all agreed that PNG government decision-making should draw on more representative and frequent data collection and analysis. A follow-up course with UPNG is planned for mid-Oct. 2019, where we will continue to explore and analyze the IFPRI survey data on food systems in PNG, aiming to inform national and local policies to improve rural food security.

Gracie Rosenbach is a Research Analyst and Emily Schmidt is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division.