The rise of anti-globalization politics and policies around the world poses threats to progress in efforts to end global hunger and malnutrition, according to IFPRI’s 2018 Global Food Policy Report (GFPR), released March 20 and featuring an in-depth look at antiglobalism and food systems. At the Washington, DC launch event, panelists discussed the report’s implications.

“Don’t forget, human history is a migration history,” IFPRI Director General Shenggen Fan said. “Migration helped not only the migrants, who can improve their food and nutrition security, but also their families. Not only the hosting countries, but also the source or originating countries,” he said. The GFPR explores how these substantial economic and social benefits cut against the anti-immigrant rhetoric now heard in many countries.

Fan reviewed highlights from the report, focusing on the radical challenges to the global food system from anti-globalization sentiments—including trade protectionism, threats to investments, tightening borders, restrictions on the flow of knowledge and data, stalled farm policy reforms, and weak global governance.

The effects of globalization are positive yet uneven, and that creates political stresses, said Shanta Devarajan, acting chief economist and senior director for development economics, World Bank Group. “For every job destroyed by globalization, two are created—but the problem is they are not the same people,” he said. One result of those stresses is policy uncertainty, such as that surrounding new U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum. “If countries retaliate up to the maximum allowed by World Trade Organization rules, that could lead to a decline in global trade of 10 percent—as large as the decline during the Great Recession,” Devarajan said.

Dan Glickman, executive director of the Aspen Institute Congressional Program, warned that raising import tariffs could gravely impact the ability of U.S. industries to sell products in international markets—in particular, agriculture, aviation, and entertainment. (Chapter 3 of the GFPR deals with this shifting trade landscape.)

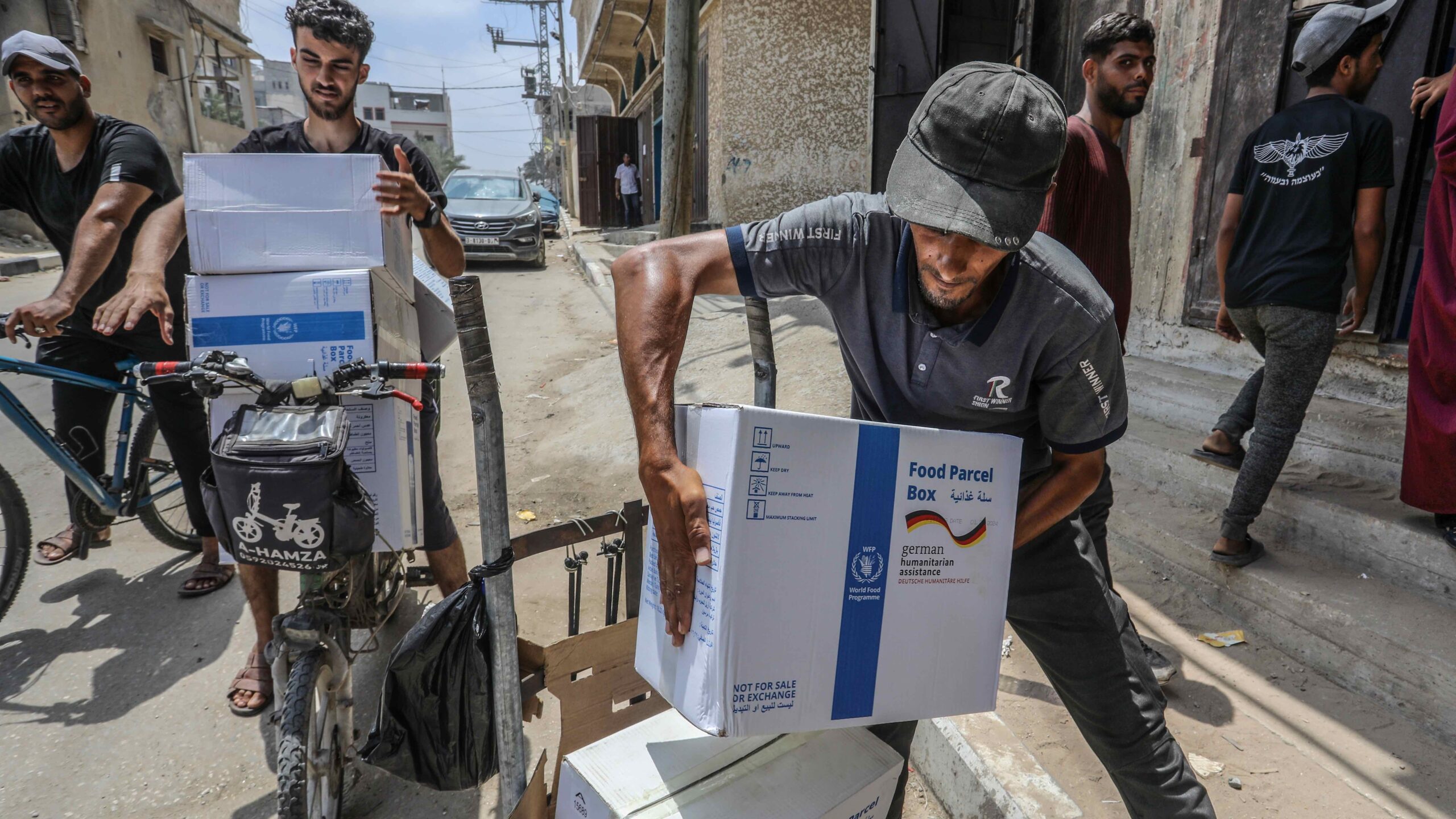

Meanwhile, he said, weak or ineffective governance impedes progress on addressing hunger and malnutrition around the world. “You can’t do anything globally without dealing with corruption and governance issues,” Glickman said. For instance, he noted that historically, the U.S. has a good track record in ensuring a commitment to humanitarian assistance, yet there is a country in its own hemisphere —Venezuela—where chronic political and economic instability have helped displace as many refugees as Syria in aggregate terms. This problem has gone largely unaddressed despite its enormous implications, he said.

Catherine Bertini, a distinguished fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, noted that many countries lag in reforming food systems and in reducing hunger and malnutrition, and that international organizations have not been able to fill this gap. “Where is the political will?” she asked, commenting on chapter 8, which addresses governance reform.

Typically, Bertini said, several large international organizations are created to address a specific issue and then fail to coordinate their programs and actions, resulting in chronically weak global governance. One way to address this problem, she said, is to fund specific research targeted at member states and focusing on key topics. This approach can help countries see how cooperative action on a given issue benefits their citizens. Democracies are motivated when they can see such direct benefits to multiple interests, she said.

“Food can fix it,” said Food Tank President Danielle Nierenberg, reiterating a theme of chapter 2: Food and food systems are essential to addressing problems of nutrition, health, and poverty—but those systems must respond to evolving global challenges. New food and agriculture technologies are part of that, Nierenberg said, and the best of those combine new advancements with indigenous and traditional knowledge. And where national governments and international organizations may fail to lead on food issues, she said, many cities and municipalities are taking a leading role in developing action plans around food access and affordability.

Open data—the topic of chapter 6—is a key tool for researchers and policy makers trying to build better food systems, panelists agreed. Getting information to the general public to allow evidence-based decision making can help generate the political will necessary to move forward, Deverajan said.

“We must encourage an open, efficient, and fair trading system … and break the vicious cycle of conflict, food insecurity, and migration” Fan concluded. “The integration of national food systems will be key to progress but will require robust evidence, good governance, and strong commitment from the international community.”

Katarlah Taylor is an IFPRI Senior Events Specialist.